When I started coaching endurance athletes in 1980 training was pretty simple. It didn’t take much to be a coach. The technology consisted of a stopwatch, a telephone and a postage stamp. Everybody I coached lived within 15 miles of me. Coaching was pretty much a guessing game since there wasn’t much training data. The athletes would tell me how training had been going in our weekly conversations and from that I’d design the next weeks’ training programs and mail it to them.

In 1983 I got my first heart rate monitor, a Polar which I still have, and began to slowly figure out how to use it. By 1986 I required everyone I coached to have one. Some balked at this at first but they eventually went along with me and began to see the benefits of “high tech” training. A couple of years later I got a fax machine which made it much easier to get training programs to athletes I coached and for them to get their training logs to me. Every Monday morning my office desk would be covered with rolled-up, heat sensitive, fax paper copies of their logs for the previous week.

By 1989 my clientele began to expand outside of Northern Colorado where I lived at the time. In the early 1990s I had clients in Wyoming, Arizona, California, New York City, Florida, British Columbia, and the Cayman Islands. Communication was becoming a major issue in coaching. But fortunately, about this time email came along and athlete-coach communication improved considerably. I was still guessing at what to have the athlete do in training, though. I was only slightly more affective than I had been 10 years earlier.

In 1995 I got my first power meter—an SRM that was loaned to me for three months by Uli Schoberer, the inventor of the SRM a few years earlier. I had heard about Greg LeMond using an SRM in the last year or so of his career and I was intrigued by the concept without really knowing much about it. By the end of that summer I was thoroughly convinced that power was the future of bike training. But I couldn’t afford to buy one. Then in 1998 I got a call from a mechanical engineer in Massachusetts. He had invented something and wanted to fly to Colorado to show it to me. It was the PowerTap power meter. He gave me one of the first prototypes and so I was back to training with power again. And it’s been that way ever since.

Shortly after I began requiring all of the athletes I coached to have power meters. Some balked at it as it was too “high tech.” Most believed a heart rate monitor was all that was needed (how things had changed!). Each soon learned the benefits of training with power and became completely sold on it. Podium results have a way of doing that.

About that same time—1992, I believe—Timex, and later Garmin, came out with GPS devices for runners. The benefits of GPS were obvious once I tried it out. That soon became a requirement for my triathletes, also. But now I was becoming overwhelmed with data.

Around 2004 I found out about Cycling Peaks software (now known as WKO+™). For the first time I was able to thoroughly interpret power and heart rate data. This was based largely on the ideas of Andy Coggan, PhD, who developed the Training Stress Score (TSS) concept which allowed a much more in-depth analysis of power data. More recently running TSS has made it possible to analyze running with WKO+ the same way as with power. TSS challenged the training methodology I had been using now for 20-some years causing me to rethink, and in some cases modify, how I trained athletes and even what I thought I knew about training. The learning curve has been steep the last two years because of TSS.

My business partners and associates at www.trainingpeaks.com are working on more technology now which will soon make me more effective as a coach and allow my athletes to race even better. The stuff they tell me they are developing is pretty exciting. I can’t wait!

Now I look back at the 1980s and wonder how I ever did it. I was shooting from the hip all the time. Back then athlete-coach proximity was the key to successful coaching. It no longer is. I don’t care where the athletes live any more so long as they speak English, are experienced and have good skills. The issue is now technology and data analysis. The more data I get from the athlete the better. Coaching has certainly changed.

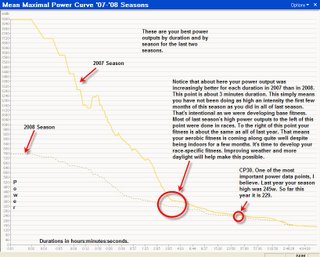

from WKO+ software shows the best Critical Power for every duration for the last two seasons for one of the athletes I coach. He is a 56-year-old who competes both as a road cyclist and triathlete. He is quite successful racing in both sports.

from WKO+ software shows the best Critical Power for every duration for the last two seasons for one of the athletes I coach. He is a 56-year-old who competes both as a road cyclist and triathlete. He is quite successful racing in both sports.