This is the time of year when I get a lot of email from athletes describing how they just did their first races of the season and were going great until a cramp came on. Should they eat more bananas, is the most common question.

That cramps are more common in the first races of the year and not in the late season probably tells us something. No matter how hard you've been training this spring the workouts are not as hard as the races are. The body simply isn't in race shape yet. By the end of the season the body has adapted to the stresses of racing and is less inclined to cramping.

But for a few athletes the problem continues throughout the year. There is no more perplexing problem for these athletes than their susceptibility to cramping. Muscles seem to knot up at the worst possible times during their important and hard-fought competitions.

The real problem is that no one really knows what causes them. There are just theories. The most popular ones are that muscle cramps result from dehydration or electrolyte imbalances. These arguments seem to make sense—at least on the surface. Cramps are most common in the heat when low body-fluid levels and the possible decrease in body salts are likely to occur.

But the research doesn’t always support these explanations. For example, in the mid-1980s 82 male runners were tested before and after a marathon for certain blood parameters considered likely causes of muscle cramps. Fifteen of the runners experienced cramps after 18 miles of the race. There was no difference, either before or after the race, in terms of blood levels of sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, hemoglobin or hematocrit. There were also no differences in blood volume between the crampers and the non-crampers. Nor were there any significant differences in the way the two groups trained.

For very long events, those lasting more than about four hours, a bit more is known. A few studies have linked these cramps to hyponatremia—low sodium levels. This condition may result from drinking large volumes of fluids that are low in sodium and may be aggravated by starting the event with low levels of sodium. Since serious athletes are particularly good at avoiding the use of salt on food, they may be highly susceptible to hyponatremia. The day before and the morning of a very long race it may be a good idea to use salt more liberally to increase the body’s levels. The sports drink used for the race should also provide adequate levels of sodium. For long races, eating salty foods may also help prevent not only cramping, but also the life-threatening symptoms of hyponatremia.

It’s interesting to note that athletes are not the only people who experience muscle cramping. Workers in occupations that require chronic use of a muscle, especially one that crosses two joints, but don’t sweat profusely as athletes do, are also susceptible. A good example is musicians who are known to cramp in the hands and arms.

So if it isn’t dehydration or electrolyte imbalance, what causes cramping? Other theories are emerging. One is that poor posture or inefficient biomechanics are a cause. Poor movement patterns may cause a disturbance in the activity of the Golgi tendon organs. These are “strain gauges” built into the tendon to prevent muscle tears. When activated, these organs cause the threatened muscle to relax while stimulating the antagonistic muscle—the one that moves the joint in the opposite way—to fire. There may be some quirk of body mechanics that upsets a Golgi device and sets off the cramping pattern.

If this is the cause, prevention may involve improving biomechanics, and regular stretching and strengthening of muscles that seem to cramp along with their antagonistic muscles.

Another theory is that they result from burning protein for fuel in the absence of readily available carbohydrate. In fact, one study supports such a notion. In this research, muscle cramps occurred in subjects who reached the highest levels of ammonia release during exercise. High ammonia levels indicate that protein is being used to fuel the muscles during exercise. This may indicate a need for greater carbohydrate stores before, and better replacement of those stores during intense and long-lasting exercise.

When you feel a cramp coming on there are two ways to deal with it. One is to reduce the intensity and slow down—not a popular option in an important race. Another is to alternately stretch and relax the effected muscle group while continuing to move. This is difficult if not impossible to do in some sports such as running and with certain muscles. Actually there is a third option which some athletes swear by—pinching the upper lip. Strange, but true.

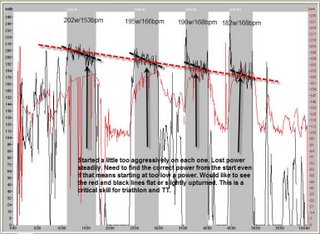

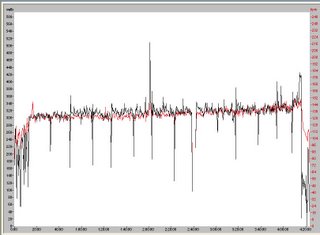

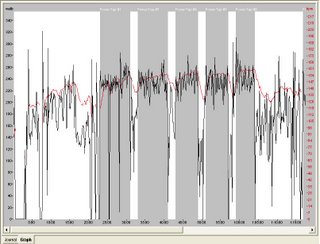

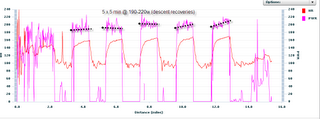

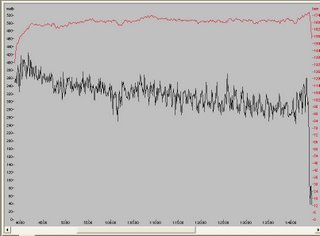

A few weeks ago I wrote about negative splitting a race and the 51-49 principle (the importance of making the first half slightly slower/easier than the second half of a race). The graph on the left is a good example of what happens when you do just the opposite--positive split the course. This is from a 65-minute hill climb done as a bike test. Notice how heart rate (red) stays steady while power (black) drops steadily. The athlete simply went out too fast. This makes for a painful race or workout that is slower than it would have been had he gone out easier.

A few weeks ago I wrote about negative splitting a race and the 51-49 principle (the importance of making the first half slightly slower/easier than the second half of a race). The graph on the left is a good example of what happens when you do just the opposite--positive split the course. This is from a 65-minute hill climb done as a bike test. Notice how heart rate (red) stays steady while power (black) drops steadily. The athlete simply went out too fast. This makes for a painful race or workout that is slower than it would have been had he gone out easier.