Weak Form and B-Priority Races

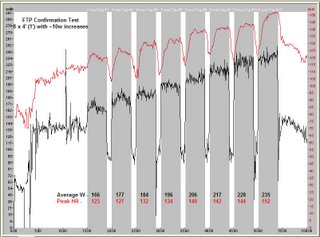

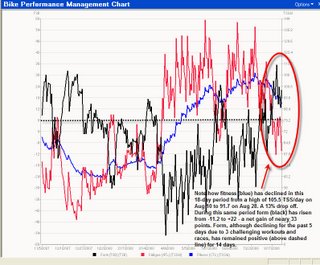

In the first chart notice how his fitness (blue graphic) has declined in the last 18 days (the portion inside the red oval). At the start of this period on August 10 his TSS/day was 105.5. That’s just below his high fitness point of the season which was at about 110 TSS/day. As of yesterday his fitness had dropped to 91.7 – a 13% loss. I’ve found that losses of 10% or less seem to be optimal when peaking. He’s outside of that range and it’s apparent.

During this same period his form (black graphic) on the first chart has risen from -11.2 to +22, a net gain of nearly 33 points. Form, although declining for the last 5 days due to 3 challenging workouts and races, has remained very positive (above the dashed line) for the last 14 days.

Having positive form almost always means that the athlete is feeling rested. But if fitness drops off too much (more than 10%) power is lost. So this explains why the athlete feels ready to race but can’t seem to produce decent results. Weak form.

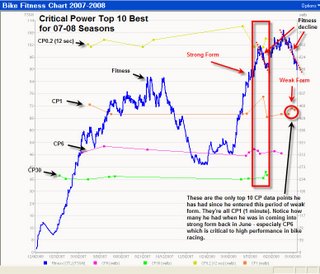

The second chart illustrates this in another way. It reflects his fitness (blue) for the last 2 seasons and also shows his top 10 best critical power (CP) values for 12 seconds (CP0.2), 1 minute (CP1), 6 minutes (CP6) and 30 minutes (CP30). Notice that most of his top 10s have been this season which starts at the low point in the blue fitness graphic. His best results of the season came when he was peaking for his A-priority race in June. This is the area within the red rectangle. Notice how many top 10 CPs occurred then. This was very definitely a period of strong form. He lost about 10% of his fitness then but was putting out some of his best power of the season, especially at CP6 which is critical to success in bike road racing. Also note how few top 10s he’s had during this recent period of time described above. Only 3 and they were all at CP1.

This is why I tell athletes that they need to limit the number of A- and B-priority races they do in a season, and preferably spread them out. Resting every week to have good results ultimately means having poor results. Keep this in mind as you start thinking about your race schedule and priorities for the 2009 season.