I recently read (actually, I listened to the audiobook) Outliers: The Story of Success, by Malcolm Gladwell. He suggests that success in any endeavor typically results from two things – luck and hard work.

He points out that luck is the result of being born at the right time and living in the right place. One of the many examples he gave for this was Bill Gates. In the late 1960s Gates was in junior high school at the time computers were just beginning to appear. He was very interested in computer technology but in order to become proficient he would have to spend a lot of time playing around with one. That wasn’t easy to do since there were very few available. But he happened to live in a place where an organization had a computer he could use any time he wanted. The time and place were perfect for him. How lucky.

He capitalized on this opportunity by spending nearly all of his spare time messing around with it. Within a matter of a few years it is estimated he logged over 10,000 hours of computer time. During his junior year at Harvard he dropped out and started Microsoft. The hard work paid off.

Luck and hard work. That’s it, Gladwell says. You have limited control over the first. It’s too late to change when you were born. If you’re a triathlete now you can thank your lucky stars to have been at an opportune time since the sport didn’t really exist until the early 1980s. Mountain biking came along in the mid-1980s. The running boom started in the early 1970s. And road cycling has only been popular in the US since the early 1970s. So, depending on your age right now, your timing may have been pretty good.

You do have some control over where you live, however. There are places that seem to produce excellent endurance athletes such as Boulder and San Diego. Why? Because they have the resources associated with endurance sport success such as decent weather, variable terrain, top coaches, adequate facilities, talented training partners, good roads, sports medicine practices, and more.

Gladwell suggests that 10,000 hours at any endeavor is what is needed to master it. Again, he offers many examples such as the Beatles. He estimates that they had played together for 10,000 hours by 1964 when they became an “overnight” success in the US as a rock band.

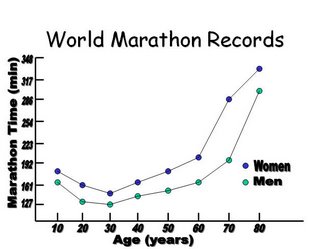

In athletic terms, 10,000 hours is 10 years of 20 hour weeks. Elite endurance athletes in cycling and triathlon typically put in more than 20 hours a week so they get their 10-grand a little sooner. If they started training seriously in their early 20s by their late 20s they are approaching their peaks. Many can keep this peak going into their 30s because they continue to become smarter as athletes. For example, they learn more about race strategies and tactics, and what works best for their own training.

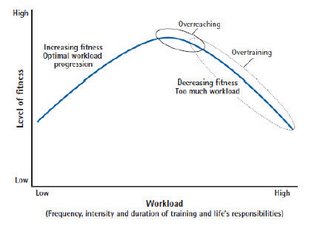

Most age-group athletes who train far less than 20 hours weekly have many years of improvement ahead of them depending on the effects of their aging curves. The older you get the fewer mistakes you can make in training if you want to keep the growth curve rising steadily. They must avoid injury, illness and other breakdowns that interrupt training. This is the biggest challenge for self-coached athletes there is. It’s a rare athlete who will limit himself. Most are intent on doing all that is possible. Hard workouts abound.

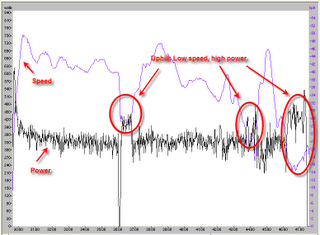

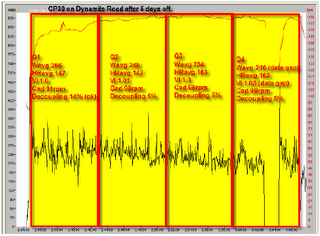

I believe that the key to success in sport is not simply hard workouts but, more importantly, training consistency — practicing your sport day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year. Uninterrupted. Athletes who focus on excessively hard workouts on the premise that this will quickly produce exceptional performance eventually find themselves overtrained, burned out, injured or sick. There is nothing that produces race results like years of consistent training. This is not to say there is no place for hard workouts. There is. It’s just a matter of how hard and how often.