I've received a number of comments and questions in regards to my recent post on Training and the Transition Period. What really stands out from these is how many of you are unwilling, or perhaps even unable, to relax at the end of the race season and take a break. There is obvious concern about gaining weight and losing fitness. I suppose this is to be expected. I can only tell you that you will never achieve a really high level of fitness until you learn to accept low levels of fitness. As with many things in life, the lower your lows, the higher your highs. Let go and relax for two to six weeks after your last race. You'll race better next year. I've seen it happen many, many times before with athletes who were reluctant but forced to rest. Now back to the business at hand...

Two days ago I posted Part 1 of this overview of how to plan out a season. I also suggested that you download a free Annual Training Plan (referred to as an 'ATP' below) at TrainingBible Coaching or sign up for an account at TrainingPeaks where all of this ATP heavy lifting will be done for you by the VirtualCoach I designed. Now back to the planning process...

Step 1: Determine Goals for 2010

At the top of the ATP are spaces for three seasonal goals. I’ve found that three is about right. When there are too many goals something gets neglected. You can have fewer, but I’d suggest no more than three.

Goals should be event outcomes, not vague statements about your dreams of success. They should be well-defined by including one basic element — what exactly you want to achieve in given races. Goals such as to lose weight and improve power or pace are actually training objectives, not goals, which we’ll get to in a while. These are things that will help you to race better in some way. If you are training to race then state your goals around what you want to accomplish in those races. If you don’t care about the outcomes of races (or other events such as century rides) then you can make your goals whatever best fit your interests.

Goals should also be measurable. It isn’t enough to set a goal of “Race faster.” Goals should be more along the lines of, “Complete the XYZ Time Trial on May 7 in less than one hour.” The more tightly you define your goals the easier you will find it is to work toward their successful accomplishment. I've always been a firm believer that the more precisely you state your goal the easier it will be to achieve.

Of course, a goal to win the local road race or triathlon has a lot to do with who shows up that day and how fit they are. It is often better to set a performance-related goal, such as a time or strategy that you believe will win the race. The exception is when you know exactly who the competition is likely to be and what they are capable of doing in a race.

Write your three goals for 2010 in the spaces provided at the top of the ATP.

Step 2: Establish Training Objectives

Can you achieve your goals? There should be at least a seed of doubt in your mind or the goal is too easy and won’t really be fun to achieve. If there is no question at all about your potential for success then the goals aren’t going to challenge you and training will have little purpose.

Here’s something for you to ponder: Why can’t you achieve your goals now - without even training? If you knew you could achieve them now we’d call them accomplishments rather than goals. Since there is uncertainty about your capacity to perform at the level of the Big Goal there is obviously something lacking that stands between you and immediate success. The purpose of your training is to ‘fix’ this performance ‘limiter.’ The sub-goals that will lead you to doing this are called ‘training objectives.’

A limiter is not merely a weakness; it’s a race-specific weakness. For example, you may have a weakness when it comes to racing on hilly courses. But if your A-priority races are all flat then this weakness is not a limiter. If we know what your limiters really are and you train in such a way as to make the limiters stronger then you will be able to achieve your goals. It’s that simple.

The key question is, what are my limiters? Answering this question is the single most important thing you can do right now to move toward achieving your goals. Most athletes never ask this question. They train absentmindedly doing whatever seems right at the time. If they are strong believers in hill work they do lots of hills. If long, slow endurance is their favorite way to train then that’s what they do. It never dawns on them that until they improve whatever it is that is holding them back there will never be a performance breakthrough. Continuing to focus on strengths while ignoring limiters means there will be little or no change in performance.

So, what are the possible limiters? They are nearly endless including everything that affects athletic development in such broad categories as training, lifestyle, nutrition, time available for training, athletic equipment, training environment, support, susceptibility to illness and injury, poor tactics and strategy, lack of race experience, poor body composition, insufficient sleep and psychological stress. While you need to examine yourself in terms of each of these categories, we will concern ourselves here primarily with limiters that can be strengthened with training.

Training is something we do to improve performance abilities. In The Triathlete’s and Cyclist’s Training Bibles I describe six abilities that determine how successful one is as an athlete. They are

• Endurance — the ability to keep going for a very long time. Improved by doing long workouts, especially in zone 2.

• Force — the ability to overcome resistance. Improved by training with weights, on hills, against the wind, and in rough water.

• Speed skills — the ability to make the movements of the sport in an economical and effective manner. Improved with drills, fast repeats of a few seconds, plyometrics, and high-frequency training.

• Muscular endurance — the ability to go for a moderately long time at a moderately high effort (at or just below lactate/anaerobic threshold). Improved with long (6-12 minutes) intervals with short recoveries, or long (20-60 minutes), steady efforts done in zones 3 and 4.

• Anaerobic endurance — the ability to go for a relatively long time (a few minutes) at a very high effort (well above lactate threshold). Improved with short (2-4 minutes), fast intervals with about equal recovery durations done in zone 5b (CP6).

• Power — the ability to sprint at very high outputs for a few seconds. Improved with very short (less than 20 seconds), max effort sprint intervals with long recoveries (several minutes).

For novice athletes the first three, the ‘basic’ abilities, are the typical limiters. For experienced athletes who have devoted three or more years to improving endurance, force and speed skills, the common limiters are the ‘advanced’ abilities — muscular endurance for longer events, anaerobic endurance for shorter events, and power for sprinting. The power ability is seldom an issue in triathlon.

The following are some examples of training objectives listed by ability. These may give you some ideas about what yours might be. Give this some thought and then list your training objectives at the top of the ATP below Goals. There is room for five. You’ll need at least one objective for each limiter. Be sure to indicate when you need to achieve the objective. That will keep you honest so they don’t just become ‘maybe’ dreams. This date should be in advance of your most important race for which that improved ability is needed for success.

Endurance Objective example: Within a six-week period complete six, four-hour rides in zone 2 with the last on July 8.

Force Objective example: Freebar squat 1.5 x body weight by January 7.

Speed Skill Objective example: Complete a 5k running race with an average cadence of 88 by August 12.

Muscular Endurance Objective example: Take 30 seconds off of 3km run done at a heart rate 10 bpm below lactate threshold by September 2.

Anaerobic Endurance Objective example: Improve CP6 to 330 watts by June 17.

Power Objective example: Average 800 watts for at least 12 seconds by August 30.

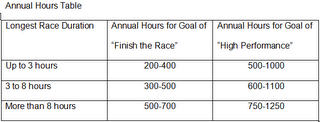

season. You may be able to add 10 to 15 percent onto this number for 2010 if you successfully and easily managed that volume. Another way of estimating annual hours is to determine what your normal training hours are for a week and multiply that by 40. A third option is to base annual hours on your longest race and general goal for that event using the Annual Hours Table.

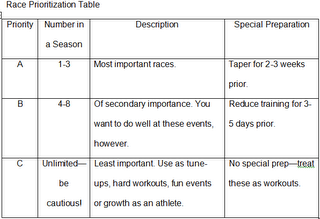

season. You may be able to add 10 to 15 percent onto this number for 2010 if you successfully and easily managed that volume. Another way of estimating annual hours is to determine what your normal training hours are for a week and multiply that by 40. A third option is to base annual hours on your longest race and general goal for that event using the Annual Hours Table. appropriate weeks based on their usual dates. For example, let’s say that you have an event scheduled for Saturday, January 30, 2010. It would be listed in the row marked 'Jan 25' since that row includes all the dates from January 25 through January 31. If you have two races the same weekend list them both in that row.

appropriate weeks based on their usual dates. For example, let’s say that you have an event scheduled for Saturday, January 30, 2010. It would be listed in the row marked 'Jan 25' since that row includes all the dates from January 25 through January 31. If you have two races the same weekend list them both in that row.