Core Strength

About a year ago I posted a blog on this same topic. It's a topic I have given lots of thought to recently and so decided to return to it again. I'm still learning what the impact of poor core strength on cycling and swimming may be and so would appreciate any insights from readers.

We read a lot about core strength training any more, but I’ve found most people really don’t know what it means. Most seem to think it means strong stomach muscles. It goes well beyond that. Core strength could be called “torso” strength. It has to do with small and big muscles from your armpits to your groin. These core muscles stabilize the spine, support the shoulders and hips, drive the arms and legs and transfer force between the arms and legs. It’s very much akin to the foundation of a house.

When a triathlete has poor core strength it may show up in several ways. It’s most obvious in running. Poor core strength is evident in a dropping hip on the side of the recovery leg with the support-leg knee collapsing inward regardless of what the foot may be doing. Especially in running, injury is common when core strength is inadequate.

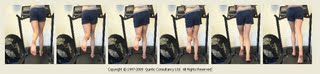

In the two sets of screen shots here you can see two athletes on treadmills running barefoot (click to expand the pictures). Notice first of all the waistline of the shorts of each runner. It indicates what the hips are doing. You’ll see that the woman’s left hip is dropping quite a bit while the man’s stays quite level to running surface. Also note the woman’s slightly collapsing right knee. The man’s is very stable. But the big surprise is their right feet. The woman’s foot has very little pronation and would be considered a stable foot. The man’s is excessively pronated (see the third screen shot).

In the two sets of screen shots here you can see two athletes on treadmills running barefoot (click to expand the pictures). Notice first of all the waistline of the shorts of each runner. It indicates what the hips are doing. You’ll see that the woman’s left hip is dropping quite a bit while the man’s stays quite level to running surface. Also note the woman’s slightly collapsing right knee. The man’s is very stable. But the big surprise is their right feet. The woman’s foot has very little pronation and would be considered a stable foot. The man’s is excessively pronated (see the third screen shot).

This is backwards from what we have always been taught to believe about the foot and what happens up the chain. Excessive pronation is supposed to cause unstable knees and hips. Stable feet should not result in hip drop and medial knee wobble. The difference is core strength. The woman’s is poor and so even her feet can’t help. The man’s core is strong and overcomes a foot that would normally cause all sorts of injury problems. And in this case the man is known to have no history of injuries and is an accomplished marathoner. The woman, despite her excellent foot stability, has experienced illiotibial band injuries. Core strength is the difference. The man has it; the woman doesn’t.

For swimming and cycling it is less obvious. Poor core strength in swimming may result in “fishtailing” – the legs and hips wiggle from to side as the hand and arm “catch” is made. Sometimes this is due to faulty stroke mechanics, so it’s hard to differentiate. But poor stroke mechanics may even result from poor core strength in thi case.

In cycling poor core strength can show up as a side-to-side rocking of the shoulders and spine when the pedal is pushed down, even when the saddle is the right height and the rider is not excessively mashing the pedals. This is generally most evident when climbing seated.

There is little doubt, even if it’s not always obvious, that poor core strength results in a loss of power in all three sports.

How do you know if your core strength is adequate? One way is to have a physical therapist do a physical assessment. Find one who works with endurance athletes and tell him or her that you would like a head-to-toe exam to pinpoint weaknesses and imbalances that could reduce performance or lead to injury. And also find out what is recommended to correct any problems found. These fixes may be strengthening exercises, flexibility exercises or postural improvement. This is perhaps the best way of finding out, but there is a cost. The exam generally takes about an hour. I have each of the athletes I coach do this every winter. It’s provides a great start on core strength training.

While quite a bit less effective, another way is to have someone video tape you while running looking for the dropping recovery-side hip shown above. You’re likely to miss the details as for the untrained eye there appears to be little difference in techniques even when the movement faults are gross. Use a treadmill and shoot the video from the back. Tuck your shirt in so you can watch the waistband of your running shorts on the video to see if it dips when the recovery leg swings through. And check the knee of the support leg to see if it is buckling in slightly. You will probably have to view this in slow motion several times to see the unwanted movements if there are any.

If you go the self-help route and determine that you need to improve core strength I’d recommend picking up Core Performance Endurance by Mark Verstegen. This is one of the best books I’ve found on core strength training for endurance athletes.

Special thanks to Mark Saunders, physiotherapist and Director of Physio4Life in Putney, UK, for the pictures and introduction to this concept.

Labels: core strength